Gross National Happiness – Running Bhutan’s Himalayan Kingdom Half Marathon

The day dawns gently over the Paro valley as I stretch and peer out over the valley from the chalet amongst the pines. Below me the expanse of rice paddy fields and small farms watered by the Paro Chhu River slowly comes to life. The light strengthens and, while the valley turns a variety of green hues in response, the pre-monsoon drizzle drops dully off the pine trees onto the pine cushion carpet outside my window. The pine needles smell fresh and invigorating in this early morning hour. Across the valley ethereal wisps of cloud caress the pine-covered Himalayan foothills and draw a brief curtain across the buttressed walls of the Paro Dzong, the fort monastery and administrative centre of this peaceful agricultural community. This idyllic visage is, however, not the reason for my early rise.

I am awake because I am in Bhutan’s mountain kingdom, a small landlocked country in South Asia located at the eastern end of the Himalayas, approximately 255 kilometres east of Mount Everest; bordered to the north by Tibet and to the south, east and west by India. I am awake at this early hour because I am running the Himalayan Kingdom Half Marathon today in a country where gross national happiness – a core Buddhist value – is a counterpoint to gross national product; where economic growth is a means to achieving more important ends such as cultural heritage, health, education, good governance, ecological diversity and individual wellbeing.

And, with calf and upper leg muscles still somewhat stiff from a climb to the prayer flag festooned Taktshang Goemba or Tiger’s Nest Monastery at 10,000 feet above sea level in Paro’s vicinity two days ago, I approach the start line to witness the unique yet simple and evocative Buddhist ceremony to bless the race. As the countdown commences all the advice and information I have gleaned to date flitters through my mind until, all of a sudden, I become focussed, and we are off into the early morning.

Running at 8,000 feet above sea level is somewhat unusual; running at this altitude for the first time is even more so. I listen to my own derived advice and start off slowly. My heart beats strongly and my breath is short as I try to find my rhythm.

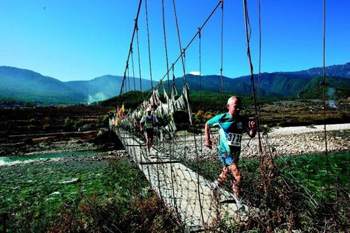

Walk, run, walk, run for the first few kilometres and then through a narrow rocky path before I break free onto a stony country road. At last, I have some rhythm now. On my right the Paro Chhu River, swollen from the overnight rains, warbles over the rounded river stones – all descendants of the great rocks and crags that thrust heavenwards into the Himalayan sky. On my left is an irrigation canal and homesteads, with resident dogs cuddled up against the chill, children in the national dress on their way to school, and farming families toiling in the paddies.

The kilometres pass by and I have settled down. But running at this altitude is hard work. I pass a few runners and we exchange friendly greetings and words of encouragement.

Then, at around the ten kilometre mark it starts to rain and with supporters cheering us on at the water point we turn away from the urbanized centre of the Paro valley and progress up a gentle ascent behind which the upper reaches are white from the previous evening’s snowfall.

The road becomes somewhat stony now and more care must be exercised over the surface. I reach the fourteen-and-a-half kilometre mark at 7,545 feet, feeling strong ahead of the four kilometre climb to the highest point of the race.

I am part of a group of runners and our progress ebbs and flows as we come to the realization that this is a serious, serious climb. Walk, run, walk, run as the route continues to ascend, leaving the tarred surface behind until even the dust surfaced road gives way to what can best be described as a basic trekking path. The narrow path ascends past irrigation furrows then alongside a fence until it winds through thick brush and the ever-present pines. Upwards, ever upwards and, just as I thought it would level off far above the Paro Dzong, the path edges upwards once again. My calf muscles are threatening to seize up on me now as I coax myself ever upwards until the gradient eventually tempers and I have crested the hill at 8,313 feet.

I rapidly realize that with just over two kilometres to go there is little likelihood of a swift descent. The track is very narrow, without any camber and at one point it runs dangerously close to barbed wire fencing, while at other points the descent to the valley below on my right is best described as cliff-like. A missed footing, or a wrong turn and one could end up far from the designated route within seconds.

I hear the footfalls of a fellow runner behind me and listen to the question that is on every runner’s mind as we descend to the valley floor: ‘When will this punishing bush path end?’

‘Focus, take one step at a time and the descent will inevitably end,’ I reply as we pass the route markers and check points with leg muscles straining against the pull of gravity. And then, almost unexpectedly, I burst out of the bush onto a tarred road at the twenty kilometre mark and utter a primeval cry of joy, knowing that the end is near. My fellow runner passes me and down the road I go, switchbacks and wet surface and all until race officials, well-wishers and finishers clap me across the finish line.

I have conquered the altitude, the notorious hill and my tired calf muscles. But, more importantly, I have once again conquered myself, as our greatest victories are always over ourselves. What a feeling of euphoria and accomplishment! The Himalayan Kingdom Half Marathon is tough but every finisher knows full well that they have been tried and tested and that they have overcome the adversity. After all, isn’t this why we run?